Time to love.

Time to live.

Time to say goodbye.

"Every extra day I had with mum was a miracle - one made possible by heart research." - Beth

When I think about my mum, Maureen, I think about her laughter, her gentle kindness, and the extraordinary courage she showed through life’s hardest moments.

I also think about the gift of time. Eleven extra years - that’s what we were given because of advances in heart research. Eleven years that changed everything.

Mum seemed healthy for decades. We had no idea a silent heart condition had been building inside her for more than 40 years, the the result of rheumatic fever - an inflammatory disease that can occur in children after an infection and cause long-term damage to the heart. Mum underwent three open heart surgeries. Each one was gruelling, terrifying and uncertain - but each one gave us more moments together. Without them, she would never have lived to meet her granddaughter, Maya.

The bombshell diagnosis came when she was just 56. Tests revealed that her heart valves were

failing - the result of rheumatic fever. Without surgery, she had only weeks to live.

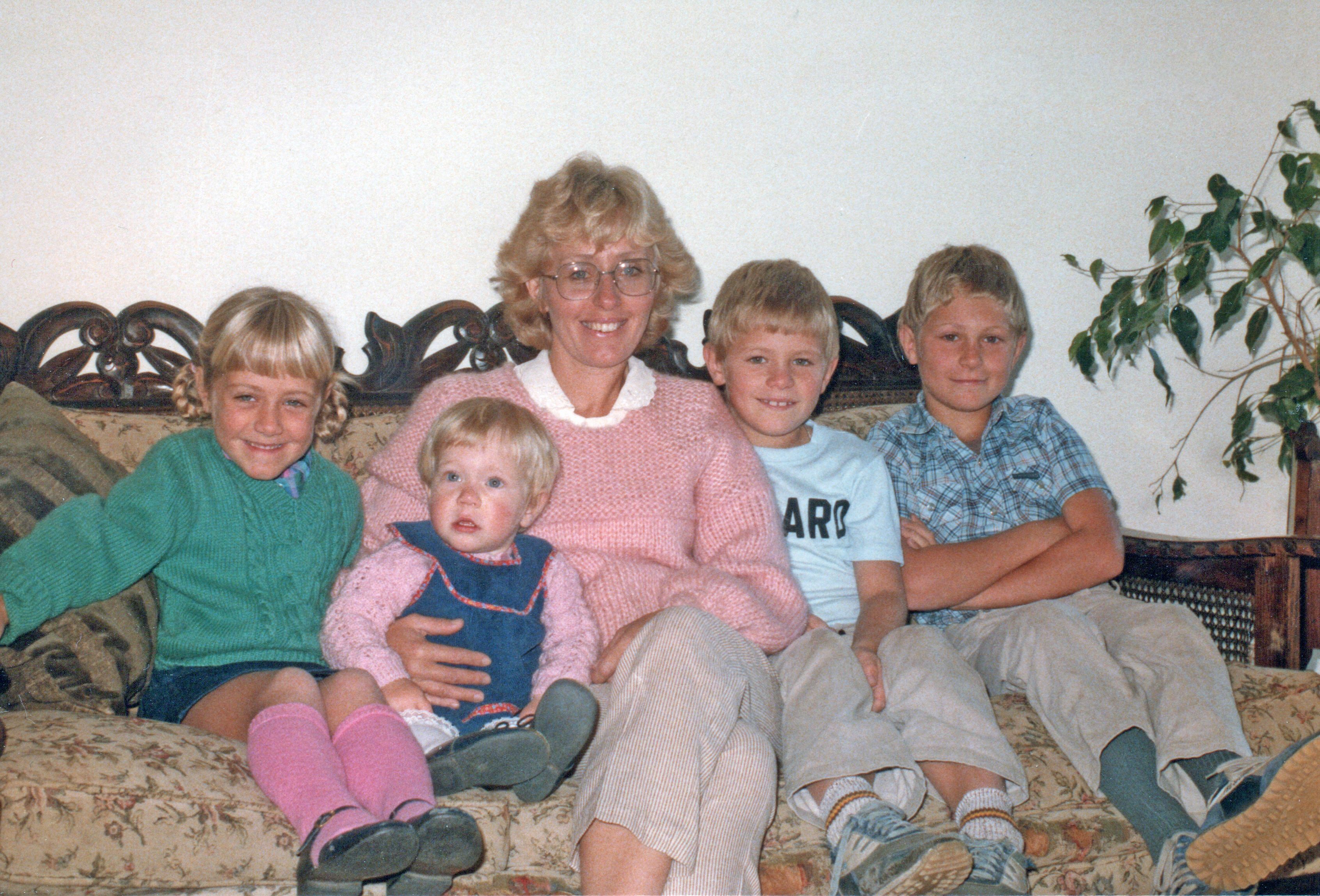

Maureen and Beth

Maureen in 1973

Maureen and Chris in 2016

It was a five hour operation. I was 26, sitting in the waiting room with Dad, trying to comprehend the enormity of what was happening.

Seeing her afterwards, I was confronted by the sight of all the tubes and machines surrounding

her. How fragile we are, and yet, when given access to the right technology and care, how resilient and strong the body is in fighting back.

That first surgery transformed her...

We often speak of the physical aspects of surgery, but what I witnessed with mum’s open heart surgery was also an emotional opening to life with a new found fearlessness, courage and determination. Our family watched mum step wholeheartedly into the creative and tenacious woman that was always within, but in facing her mortality was given permission to shine.

In her recovery she started sewing, felting and making textile art - creating vibrant and expressive, free-form artworks and handmade bags and exhibiting these with local artists. She modelled to me what it is to face fear head on and use it as an opportunity for transformation and to embrace life in all of its ups and downs.

Maureen at her sewing station

Felted pear created by Maureen

I’ll never forget the night she called me in to listen to the ticking of her new mechanical valves. With tears in her eyes, she laughed,

“Listen to this, Beth. I feel like the Terminator!”

That sound, once strange, became a source of comfort and some years later, my daughter Maya would fall asleep to the gentle ticking

inside her grandmother’s chest.

But Mum’s battle wasn’t over. She faced two more surgeries. A heart attack caused by debris from an earlier operation, and later, the valves falling out after a severe liver cyst infection. Once again, her chest was opened, her body traumatised. Once again, she pulled through.

By the third surgery, she was in her sixties and had to wait weeks for one of the few surgeons skilled enough to attempt the risky operation.

It was dire. We didn’t know if she’d make it. But she did.

Each time, she fought back. And each time, science, technology and medical skill gave her back to us.

Those final years were perhaps the most precious of all. She travelled. She created. She laughed. She embraced life. She became a grandmother.

Every heartbeat of those 11 years was a gift.

Maureen with daughters Beth and Anna and granddaughter India

Maya with photo of Maureen

Turning hope into heartbeats

That’s why researchers like Professor Julie McMullen, one of Australia’s foremost heart scientists, are working tirelessly to uncover new ways to prevent and treat heart attack and heart failure.

After more than 25 years dedicated to understanding the heart, Professor McMullen made a world-first discovery identifying a gene critical for exercise-induced protection.

Now, her team is developing innovative therapies that could replicate these benefits in people with heart disease — offering new hope to those living with heart failure.

Professor Julie McMullen (centre) and her team

“We’re trying to mimic the beneficial effects of exercise in a failing heart,” says Professor McMullen. “The goal is to reproduce the actions of the ‘good’ genes in the diseased heart.”

For Professor McMullen, this work is deeply personal.

“My grandmother had high blood pressure and heart failure. I remember helping her sort through all her tablets each morning — she hated it. She became breathless due to her failing heart and could no longer continue activities she enjoyed, such as gardening.”

That experience drives her determination to make a difference, every day.

“Despite significant advances in survival, current drugs remain limited in terms of improving heart function or quality of life. We urgently need new therapies to help people live longer, fuller lives.”

Professor Julie McMullen